Ionocaloric Refrigeration

February 27, 2023

The baseline

standard of living has vastly increased from the

mid-20th century to the present day. In the 1955-1956

television sitcom,

the honeymooners, the principal

characters, Ralph Kramden (played by

Jackie Gleason, 1916-1987) and his wife Alice (played by

Audrey Meadows, 1922-1996) lived in a

spare two room

apartment with no

telephone and an

ice box for

refrigeration. Today, people would think themselves to be

abused if they didn't own a

smartphone, have a

widescreen television, and an electric

refrigerator/freezer well stocked with

junk food.

Our present

cozy lifestyle is a direct consequence of the

labors of the many

scientists and

engineers who have created our

technological society. The technological advances in refrigeration are a good example of our progress, and there's a

website that lists a

timeline of events in refrigeration

history.[1] Some of these are as follow:

• 1834 - Jacob Perkins (1766-1849), who is known as the father of the refrigerator, is granted the first patent for a vapor-compression refrigeration system.

• 1906 - Willis Carrier (1876-1950) patents the modern air conditioner.

• 1923 - Kelvinator attains 80% of the electric refrigerator market.

• 1926 - General Electric markets the first hermetic compressor refrigerator.

• 1926 - Albert Einstein (1879-1955) and Leo Szilard (1898-1964) invent a refrigerator having no moving parts.[2]

• 1955 - 80% of American households have a refrigerator.

• 2005 - 99.5% of American households have a refrigerator.

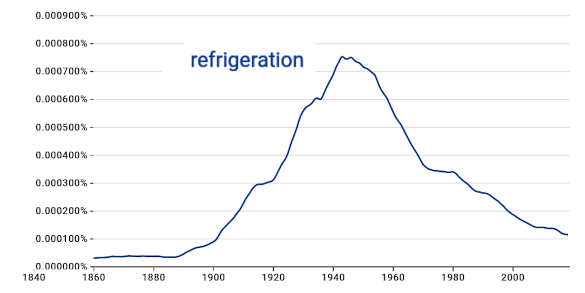

A graph of the frequency of occurrence by year of the word "refrigeration" via the Google Ngram Viewer (https://books.google.com/ngrams). The curve, not unexpectedly, resembles the graph known as the technology adoption life cycle. (Click for larger image.)

Albert Einstein, who was familiar with the patent process from his time as a

patent examiner at the

Swiss Patent Office, teamed with Leo Szilard on the

design of a refrigerator. Their

motivation was the report that an entire

family had been

killed as they

slept by leaking refrigerator

fumes.[2] The "

Einstein refrigerator" still used the

toxic refrigerants known at that time, but it was

safer since it had no moving parts and did not require

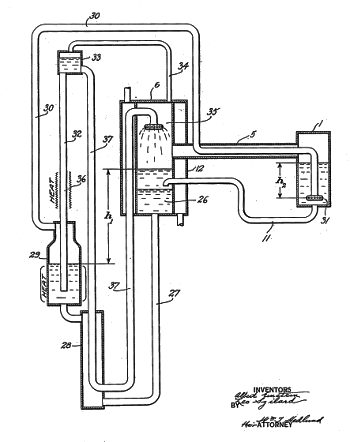

rotary seals (see figure).[3].

Figure from US Patent No. 1,781,541, "Refrigeration," by Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, dated November 11, 1930.

The "Einstein refrigerator" is an absorption refrigerator in which the cooling evaporate is absorbed by another liquid, which is run through a heat exchanger to recover the refrigerant for another refrigeration cycle.

(Via Google Patents.)[3]

The common refrigeration method, as used in

domestic and

commercial refrigerators and air conditioners, is the

vapor-compression cycle that utilizes the liquid to gas

phase transition of a

refrigerant, such as

R-600a (isobutane, HC(CH

3)

3). The refrigerant vapor is compressed, and the higher

pressure results in a higher

temperature. This hot, compressed vapor is then

condensed into a liquid by a

heat exchanger where it is cooled. The condensed liquid refrigerant flows through an

expansion valve where the abrupt reduction in pressure causes it to cool in a

Joule expansion. It then flows through heat exchanger

coils within the refrigerator to cool its interior. The interior warms the refrigerant to change it into a gas to feed again through the compressor, restarting the cycle.

Aside from the vapor-compression cycle, there are several other methods of cooling. One of these is

thermoelectric cooling in which a

thermoelectric Seebeck effect device is used in inverse to cool one

surface while heating another, rather than generating

electricity from a hot-cold temperature difference. While this has the advantage of having no moving parts, it's far less

efficient. I wrote about the thermoelectric effect in an

earlier article (Thermopower on the Cheap, December 21, 2012). Far more interesting is the

magnetocaloric effect, the subject of another of my articles (

Magnetic Refrigeration, September 3, 2014).

In 1881,

German physicist Emil Warburg (1846-1931) found that

iron, a

magnetic material, would cool about a degree

Celsius when subjected to an

applied magnetic field of one

tesla, the equivalent of 10,000

gauss.[4] The

Earth's magnetic field is about half a gauss; so the effect is very small. This effect can be used in a

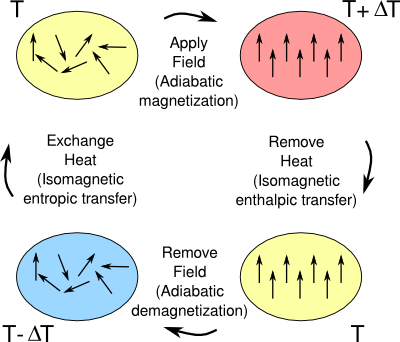

magnetic refrigeration cycle (see figure).

The thermodynamic cycle of a magnetic refrigerator.

Refrigeration is achieved by using the entropy associated with the alignment of the magnetic moments of the atoms in a solid as a heat pump.

(Click for larger image.)

The magnetocaloric effect is greatest near the vicinity of a magnetic

phase transition, and some

alloys of

gadolinium, such as

Gd5Si2Ge2, exhibit a "giant magnetocaloric effect" (GMCE) around

room temperature.[5] I wrote about this effect in a

previous article (Giant Magnetocaloric Effect, September 10, 2018). Some of my former

colleagues worked on magnetocaloric

materials in the

1990s.[6]

A recent article in

Science describes a new refrigeration principle,

ionocaloric refrigeration, which uses

ions to drive solid-to-liquid phase transitions in a thermal cycle.[7-10] This technology was developed by

Drew Lilley and

Ravi Prasher, both at

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, California) and the

University of California (Berkeley, California).[7]

Unfortunately, even today's newer

hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants have a

global warming potential, and this problem is

exacerbated by increased use of air conditioning in our warming world.[7-8,10] Hydrofluorocarbons are

greenhouse gases that are thousands of times as powerful as

carbon dioxide.[9] A

2022 climate agreement called the Kigali Amendment commits

signatory nations to reduced

production and

consumption of hydrofluorocarbons by at least 80% over the next 25 years.[10] This has encouraged

research on on alternatives to vapor-compression refrigeration, and ionocaloric cooling is one such technology.[9]

Magnetocaloric refrigeration requires large applied fields, and they have low efficiency and offer just a small temperature change.[7,10] Ionocaloric cooling works by using ions to drive solid-to-liquid phase changes; and, having a liquid as part of the cycle makes it easier to exchange heat in the system.[9] The

researchers have

calculated that ionocaloric cooling has the potential to work at least as efficiently as vapor-compression systems.[9] The

published ionocaloric cooling system uses an

environmentally friendly salt and

solvent.[10]

The operating principle of ionocaloric cooling is the same

freezing point depression principle by which added salt will cause water to freeze at lower temperature. A

saturated solution of

salt water has a freezing point of -21°C; but, to make this large temperature change useful in refrigeration, the process needs to be

reversible.[7-8] The ionocaloric cycle used the flow of

sodium iodide (NaI) ions from

ethylene carbonate ((CH2O)2CO) as the reversible part of the cycle.[9-10] The sodium iodide is removed from the ethylene carbonate by

electrodialysis, causing the ethylene carbonate to

recrystallize and expel

heat.[10]

Animation of the ionocaloric cooling process. Electric current flow causes ions to induce a solid to liquid phase transition in a material, and the material absorbs heat from the surroundings. Reversed current flow removes the ions, causing the material to recrystallize into a solid and release heat. (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory image by Jenny Nuss.)

Experiments have shown a larger

adiabatic temperature change and

entropy change per unit

mass and

volume for the ionocaloric system as compared with other caloric effects at equivalent low applied field strengths.[7] There's a 30%

Carnot cycle efficiency and a temperature change as high as 25°C at about 0.22

volts.[7] Says study

author, Drew Lilley,

"There's potential to have refrigerants that are not just GWP [global warming potential]-zero, but GWP-negative... Using a material like ethylene carbonate could actually be carbon-negative, because you produce it by using carbon dioxide as an input. This could give us a place to use CO2 from Carbon capture."[9]

The ionocaloric cycle can be used for

heating as well as cooling.[9] What's needed before

commercialization are experiments on different combinations of materials and development of the components for an actual refrigeration unit.[9] Lilley and Prasher have filed a

provisional patent application for the ionocaloric refrigeration cycle.[9]

Research funding was provided by the

United States Department of Energy in its

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Building Technologies Program.[7,9]

References:

- Timeline of Refrigerators and Low-Temperature Technology, History of Refrigeration Website.

- Gene Dannen, The Einstein-Szilard Refrigerators, Scientific American, January 1997, pp. 90-95.

- Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, "Refrigeration," US patent No. 1,781,541, November 11, 1930 (via Google Patents).

- Anders Smith, "Who discovered the magnetocaloric effect?" The European Physical Journal H, vol. 38, no 4 (September,2013), pp 507-517.

- V. K. Pecharsky and K. A. Gschneidner, Jr., "Giant Magnetocaloric Effect in Gd5(Si2Ge2)," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 78 (June 9, 1997), Document No. 4494, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.4494.

- J. M. Elbicki, L. Y. Zhang, R. T. Obermeyer, and W. E. Wallace, "Magnetic studies of (Gd1−x M x )5Si4 alloys (M=La or Y)," J. Appl. Phys., vol. 69, no. 8 (April 15, 1991), pp. 5571ff.

- Drew Lilley and Ravi Prasher, "Ionocaloric refrigeration cycle," Science, vol. 378, no. 6626 (December 22, 2022), pp. 1344-1348, DOI: 10.1126/science.ade1696.

- Emmanuel Defay, "Cool it, with a pinch of salt," Science, vol. 378,no. 6626 (December 22, 2022), p. 1275, DOI: 10.1126/science.adf5114.

- Lauren Biron, "Berkeley Lab Scientists Develop a Cool New Method of Refrigeration," Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Press Release, January 3, 2023.

- Presenting "ionocaloric" refrigeration: A new approach to efficient and sustainable cooling, American Association for the Advancement of Science Press Release, December 22, 2022.

Linked Keywords:

Standard of living; mid-20th century; television sitcom; honeymooners; character (arts); Jackie Gleason, 1916-1987; Audrey Meadows, 1922-1996; spare; apartment; telephone; ice box; refrigeration; economic, social and cultural rights; abuse; smartphone; widescreen; television set; refrigerator/freezer; junk food; comfort; cozy; lifestyle (sociology); work (human activity); labor; scientist; engineer; technology; technological; society; website; timeline; history; Jacob Perkins (1766-1849); patent; vapor-compression refrigeration; Willis Carrier (1876-1950); air conditioning; air conditioner; Kelvinator; electricity; electric; market (economics); General Electric; hermetic seal; hermetic; gas compressor; Albert Einstein (1879-1955); Leo Szilard (1898-1964); invention; invent; moving parts; United States; American; household; chart; graph; statistical frequency; frequency of occurrence; year; word; Google Ngram Viewer; curve; technology adoption life cycle; patent examiner; Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property; Swiss Patent Office; design; motivation; family; death; killed; sleep; vapor; fumes; Einstein refrigerator; toxicity; toxic; safety; safer; rotary seal; absorption refrigerator; evaporation; evaporate; absorption (chemistry); liquid; hydraulics; run through; heat exchanger; thermodynamic cycle; Google Patents; home; domestic; commerce; commercial; vapor-compression cycle; phase transition; refrigerant; isobutane; R-600a; pressure; temperature; condenser (heat transfer); condensed; thermal expansion valve; Joule expansion; coil; thermoelectric cooling; thermoelectric effect; thermoelectric Seebeck effect; surface; electric power; efficient energy use; magnetocaloric effect; Germany; German; physicist; Emil Warburg (1846-1931); iron; magnet; magnetic material; Celsius; applied magnetic field; tesla (unit); gauss (unit); Earth's magnetic field; magnetic refrigeration cycle; thermodynamic cycle of a magnetic refrigerator; entropy; angle; alignment; magnetic moment; atom; solid; heat pump; alloy; gadolinium; silicon; room temperature; colleague; material; 1990s; Science (journal); ionocaloric refrigeration; ion; Drew Lilley; Ravi Prasher; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, California); University of California (Berkeley, California); hydrofluorocarbon; global warming; exacerbate; greenhouse gase; carbon dioxide; 2022 climate agreement Kigali Amendment; signatory; nation; manufacturing; production; consumption (economics); research; researcher; calculation; calculated; scientific literature; publish; environmentally friendly; salt (chemistry); solvent; freezing point depression; solubility; saturated solution; saline water; salt water; reversible process (thermodynamics); sodium iodide (NaI); ethylene carbonate ((CH2O)2CO); electrodialysis; crystallization; recrystallize; heat; animation; ionocaloric cooling; electric current flow; Jenny Nuss; Experiment; adiabatic process; entropy; mass; volume; Carnot cycle efficiency; volt; author; carbon capture; central heating; commercialization; provisional patent application; funding of science; research funding; United States Department of Energy; Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Building Technologies Program.