Bolometry

July 29, 2019

Every

electrical engineer knows how to determine the

electrical power P dissipated by a

resistor. You measure the

voltage E across the resistor and the

current I flowing through it, then use the

formula,

P = EI. You can take a shortcut in the measurement by using the formula,

E = IR, to create the alternative power formulas,

P = I2R and P = E

2/R.

Power dissipation in a resistor.

The important variables are the resistance (R, ohms), the voltage (E, volts), and the current (I, amperes).

Since the voltage, current, and resistance are related by the formula, E=IR, there are alternative expressions for the power, as shown.

(Click for larger image.)

These simple expressions serve electrical engineers quite well in their usual tasks of

circuit design, but

power comes in many guises in the

physical world. Power is measured in

watts in

homage to

James Watt (1736-1819) of

steam engine fame, but the general form of power is

kg·

m2/

s3, which makes more sense when written (kg·m

2/s

2)/sec, since power is

work done per unit of

time, and work is in units kg·m

2/s

2. Power can be expressed in other forms, as detailed below.

While the calculation of the electrical power dissipated in a

DC circuit is easily realized through use of a

voltmeter and an

ammeter, the general problem of measuring power, itself, as with some sort of

power meter, takes more effort. Interestingly, effort is defined as the amount of work involved in achieving something, and work is a component of power.

Radiant power, such as the power captured from the

Sun, is difficult to measure. Radiant power, often called the radiant flux, is the energy

emitted,

reflected, transmitted or received, per unit time.

If you're a

physicist faced with such a measurement, the

idea of a

black body immediately comes to mind. A black body absorbs incident

electromagnetic radiation at all

wavelengths, and its

temperature will rise according to the

heat capacity of the

material from which it's made. This means that a temperature measurement becomes a power measurement. The most common

device used to measure radiant power is the

bolometer, a device that captures incident electromagnetic radiation to heat a material, much like a black body, so that radiant power can be measured by measuring temperature.

The bolometer, the name of which derived from the

Greek words, βολη (ray) and μετρον (meter), was

invented by

American astronomer,

Samuel Pierpont Langley (1834-1906), in 1878, and it was

published shortly thereafter.[1] Langley's bolometer consisted of two

platinum resistance thermometers coated with

soot so that they would act as black bodies. One of these resistors was exposed to a radiant source, while the other was

shielded, and the resistance difference between these two was detected by a

Wheatstone bridge to indicate the received power.

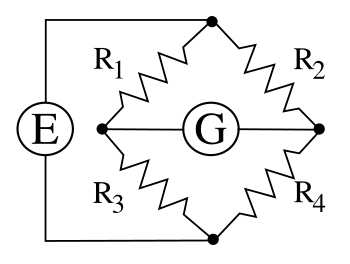

Wheatstone bridge circuit.

This circuit is named after English scientist, Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875), who popularized an original 1833 concept by English polymath, Samuel Hunter Christie (1784-1865). Wheatstone was also the inventor of the Playfair symmetric key cipher

In this circuit, the resistor pairs, R1/R3 and R2/R4 act as voltage dividers. When R1=R2 and R3=R4, the voltage at the galvanometer G is zero.

Large voltages E and a sensitive galvanometer enable measurement of a very small change in any resistor. Sensitive measurement of radiant power is possible when R1 and R2 are the radiated and shielded resistors of a bolometer.

(Created using Inkscape. Click for larger image.)

The bolometer was an advance over

thermopiles, series-connected arrays of

thermocouples, that were used for the same purpose. Using his sensitive bolometer, Langley discovered new

atomic and

molecular absorption lines in the

infrared, and he made a temperature measurement of the

Moon. In 1896,

Swedish physicist and

chemist,

Svante Arrhenius (1859-1927), used the

lunar measurements of Langley and others to calculate the extent that

carbon dioxide and

water trap infrared radiation on

Earth.

Langley invented the bolometer to detect visible and infrared light, but nearly coincident with his invention were the discovery of

X-rays by

Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, and

radioactivity by

Henri Becquerel in 1896. A bolometer will also act as a detector for these radiations if they are

absorbed in the resistive elements, since they will also cause heating. Since bolometers are slow to thermally

equilibrate with the

environment, they will effectively

integratee such radiation for increased sensitivity.

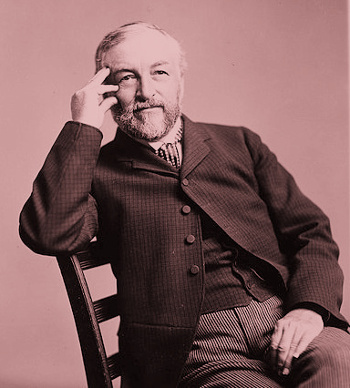

Samuel Pierpont Langley (1834-1906), circa 1895.

In his paper describing the bolometer, Langley writes, "I have entered into these preliminary remarks as an explanation of the necessity for such an instrument as that which I have called the Bolometer (βολη μετρον)... Impelled by the pressure of this actual necessity, I therefore tried to invent something more sensitive than the thermopile, which should be at the same time equally accurate, - which should, I mean, be essentially a "meter" and not a mere indicator of the presence of feeble radiation."[1]

Langley was the first director of the Allegheny Observatory (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), where he established a time distribution system essential to government and the railroads.

Langley was also an aviation pioneer for whom Langley Field, Newport News, Virginia, was named.

(Wikimedia Commons image from the Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 15, Folder 8, modified for artistic effect.)

While platinum was the best bolometer material during Langley's time, there are better materials available today.

Vanadium pentoxide (V

2O

5) has a high

temperature coefficient of resistance up to -3%/°C.[2] Also,

sensitivity is enhanced when bolometers are cooled to

cryogenic temperatures.

Microbolometers, generally created as arrays of vanadium oxide devices, are used in infrared

digital cameras. Bolometers are also used as

microwave detectors with the resistive element of the proper

impedance terminating a

stripline waveguide.

Far above the

Wi-Fi bands at 2.4 and 5

gigahertz (GHz) are the

terahertz (THz) frequencies. A terahertz is a thousand times larger than a gigahertz; and, since

semiconductor devices have difficulty operating even below 100 GHz, you can imagine the problems involved getting circuit elements to work at a terahertz. Frequencies around a terahertz exist in a so-called "

terahertz gap" between those considered to be

radio frequencies and

light. Visible light exists in the 425-775 terahertz frequency band.

The terahertz spectrum has been relatively underutilized, since it's difficult to generate terahertz radiation and also difficult making detectors at those frequencies. Since terahertz radiation will penetrate thin material layers, it's useful for

non-destructive sensing, and also for devices such as

full-body scanners. An ideal detector of terahertz radiation would have high sensitivity, a rapid response time, and it would be operable at

room temperature.

A team of

scientists and

engineers from the

University of Tokyo (Tokyo, Japan), the

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (Tokyo, Japan), and

Chung-Ang University (Seoul, Korea) has just advanced terahertz detector

technology by developing a bolometer for terahertz radiation.[3-4] Their bolometer is a

thermomechanical device that's applicable to terahertz imagers.[4]

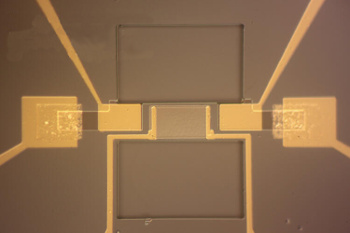

Doubly-clamped MEMS resonator bolometer.

Heating of the resonant beam by terahertz radiation changes its resonant frequency, which is easily detected.

(University of Tokyo image, simplified)

The bolometer is a doubly-clamped

microelectromechanical beam resonator that's made from

gallium arsenide using standard

MEMS processing techniques.[3] Heating by terahertz radiation

expands the beam very slightly, and this changes its resonant frequency.[4] Says corresponding author of the

paper describing this work,

Kazuhiko Hirakawa,

"Using our doubly clamped microelectromechanical beam made of gallium arsenide, we could effectively sense THz radiation at room temperature... This structure is particularly effective as it can detect THz radiation very quickly, typically 100 times faster than other conventional room-temperature thermal THz sensors."[4]

The temperature sensitivity, expressed as a

noise-equivalent temperature difference, is about 1 μK/√Hz.[3] The device is a hundred times faster than other uncooled terahertz thermal sensors in a

bandwidth of several kilohertz, which is more than enough for imaging.[3] The detection level is a

noise-equivalent power of about 90 pW/√Hz.[3]

References:

- S. P. Langley, "The Bolometer and Radiant Energy". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 16 (May, 1880 - June, 1881), pp. 342-358, DOI: 10.2307/25138616.

- Mohamed Abdel-Rahman, Muhammad Zia, and Mohammad Alduraibi, "Temperature-Dependent Resistive Properties of Vanadium Pentoxide/Vanadium Multi-Layer Thin Films for Microbolometer & Antenna-Coupled Microbolometer Applications," Sensors, vol. 19, Article no. 1320, March 16, 2019, doi:10.3390/s19061320 (Open Access PDF file).

- Ya Zhang, Suguru Hosono, Naomi Nagai, Sang-Hun Song, and Kazuhiko Hirakawa,, "Fast and sensitive bolometric terahertz detection at room temperature through thermomechanical transduction," Journal of Applied Physics, vol. 125, no. 15 (March 28, 2019), Article no. 151602, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5045256.

- Balancing the beam: thermomechanical micromachine detects terahertz radiation, University of Tokyo Press Release, May 7, 2019.

Linked Keywords: Electrical engineering; electrical engineer; electrical power; dissipation; dissipated; resistor; voltage; electric current; formula; electric power; variable; resistance; ohm; voltage; volt; ampere; electronic circuit; design; power (physics); physics; physical; watt; homage; James Watt (1736-1819; steam engine; kilogram; kg; meter; m; second; s; work (physics; time; energy; force; velocity; torque; angular velocity; direct current; DC; voltmeter; ammeter; radiant flux; radiant power; Sun; emissivity; emit; reflection (physics); reflected; physicist; idea; black body; electromagnetic radiation; wavelength; temperature; heat capacity; material; electronic component; electronic device; bolometer; Greek language; Greek word; invention; invent; American; astronomer; Samuel Pierpont Langley (1834-1906); scientific literature; publish; platinum; resistance thermometer; soot; electromagnetic shielding; shielded; Wheatstone bridge; Wheatstone bridge circuit; English; scientist; Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875); polymath; Samuel Hunter Christie (1784-1865); Playfair cipher; symmetric key; encryption; voltage divider; galvanometer; Inkscape; thermopile; thermocouple; atom; atomic; molecule; molecular; spectral line; absorption line; infrared; Moon; Sweden; Swedish; chemist; Svante Arrhenius (1859-1927); lunar; carbon dioxide; water; Earth; X-rays; Wilhelm Röntgen; radioactive decay; radioactivity; Henri Becquerel; absorption (electromagnetic radiation); equilibrium; equilibrate; environment; integral; integrate; executive director; Allegheny Observatory (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania); time distribution system; government; railroad; aviation pioneer; Langley Air Force Base; Langley Field; Newport News, Virginia; Wikimedia Commons; Smithsonian Institution Archives; vanadium(V) oxide; vanadium pentoxide; temperature coefficient of resistance; sensitivity (electronics); cryogenic; microbolometer; digital camera; microwave; electrical impedance; electrical termination; terminate; stripline waveguide; Wi-Fi; hertz; gigahertz; terahertz radiation; terahertz (THz) frequency; semiconductor device; terahertz gap; radio frequency; light; nondestructive testing; non-destructive sensing; full-body scanner; room temperature; scientist; engineer; University of Tokyo (Tokyo, Japan); Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (Tokyo, Japan); Chung-Ang University (Seoul, Korea); technology; thermomechanical; microelectromechanical system; MEMS; resonator; heat; heating; beam (structure); microelectromechanical; gallium arsenide; thermal expansion; Kazuhiko Hirakawa; noise-equivalent temperature; bandwidth (signal processing); noise-equivalent power.