Mars Landing 1976

July 18, 2016

Planetary science has come a long way since the end of the

19th century. This month, the

Juno spacecraft achieved orbit of

Jupiter, just a year after the encounter of the

New Horizons spacecraft with

Pluto. New Horizons gave us the first detailed images of distant Pluto and its

moons, and Juno will measure the

composition of Jupiter, the largest

planet in our

Solar System, perhaps even discovering whether its

clouds hide a

rocky core.

Pluto, the ninth planet, was discovered by

Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. Forty years before that, in 1890,

Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835-1910) published his detailed

map of the

surface features of

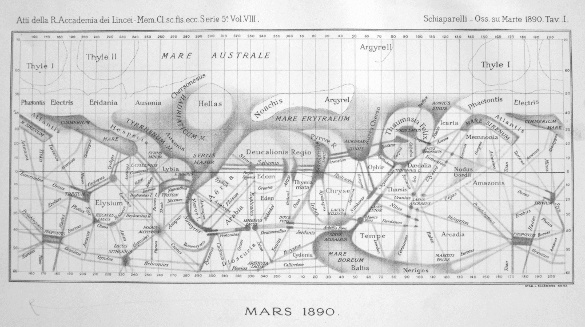

Mars (see figure). While unintended, Schiaparelli's map and the name given to the linear features he had seen launched a wave of speculation about Mars' being an inhabited planet.

Giovanni Schiaparelli's 1890 map of Mars. This map is a composite of his observations over the years 1877 to 1886. (Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Schiaparelli used the Italian word, "canali," meaning "channels" in the sense of grooves, but the similarity of this word to the English word, "canals," prompted

speculation that these were, indeed,

Martian canals built by an

intelligent race to channel

water from the

poles to

oases that were also present on this map. As

telescopes improved, such linear features were found to be just

optical illusions caused by poor viewing conditions.

Before these features were shown to be false, they inspired

Percival Lowell (1855-1916), a "

one-percenter" of his time, to build an

observatory, the

Lowell Observatory, near

Flagstaff, Arizona, a location ideal for

observational astronomy because of its isolation, high

altitude (6,900 feet), and mostly cloudless

nights. Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto at the Lowell Observatory.

Lowell popularized his

theories about Mars in three

books: Mars, 1895, Mars and Its Canals, 1906, and Mars As the Abode of Life, 1908. By these books, Lowell popularized the idea that the Martian canals were built by an intelligent life form. He had many

critics, one of whom was

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), who deserves some of the credit for the

theory of evolution by

natural selection that's typically reserved for

Charles Darwin. Wallace thought that Mars was too cold, too dry, and too airless for life.

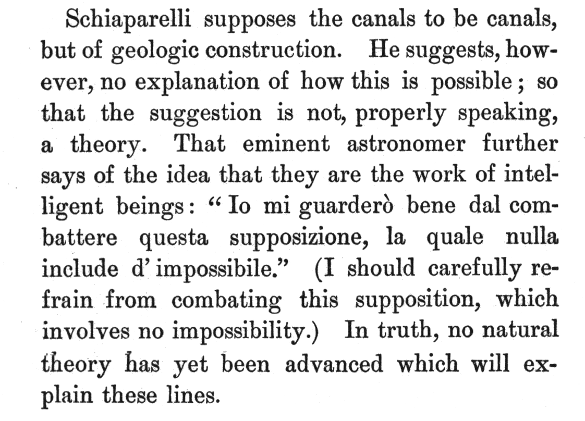

A paragraph from page 153 of "Mars" by Percival Lowell. (Scan of my copy of a facsimile edition, published in 1978, of the 1895 original edition.)[1])

Such

musing may have inspired

Edgar Rice Burroughs to write his

novels about an inhabited Mars, called "

Barsoom" by the Martians. The

plot development was assisted by the presence of a

human,

John Carter, a

captain of the

Confederacy during the

American Civil War who was transported to Mars by

some unknown process. The first novel of his Mars series was the 1917

A Princess of Mars.

Even during Lowell's lifetime, observational evidence was mounting that Mars was completely lacking in water. In mid-July, 1965, the

Mariner 4 spacecraft showed us a

cratered surface quite unlike the fanciful Mars of fiction. As an example of how far

technology has progressed in recent years, the Mariner 4 images were actually stored on a

mechanical tape recorder for

transmission back to

Earth at a necessarily slow

data rate.

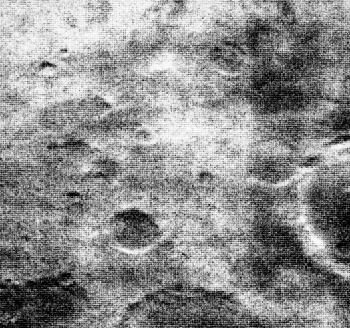

Mariner 4 image 10D, showing craters in the Memnonia Fossae region of Mars.

The image field is about 250 km x 250 km.

The crater section at the right is part of the crater, Dejnev, which is about 156 km in diameter.

(NASA image.)

Tourists would rather stop at

roadside attractions and linger, rather than catch a fleeting glimpse as they pass quickly on the

highway. Such is also true for

planetary exploration, and the Mariner 4

fly-by was followed by an actual landing on Mars. The landing was by the

Viking Lander 1 spacecraft on July 20, 1976, forty years ago.[2-4] At that landing, our

image resolution of Mars improved at least a million-fold, going from a

kilometer to

millimeter specks of

sand.

The Viking 1 lander's destination was

Chryse Planitia. A twin lander, the

Viking lander 2, arrived at

Utopia Planitia a few weeks later, on September 3. Along with the landers were

orbiters designed to image Mars at a much higher resolution than Mariner 4. Images were routinely snapped at 150-300

meter resolution, while selected areas were resolved down to 8 meters. They imaged the now familiar Martian

landscape of huge

canyons,

volcanoes, and

lava fields; and, of course, craters.

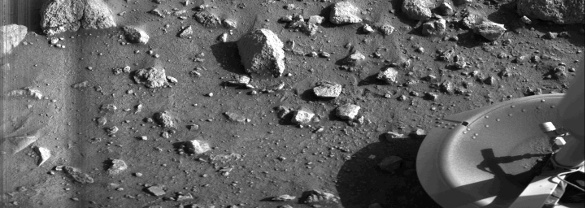

First photograph taken on the surface of Mars. The photo was taken by the Viking lander 1. (NASA image.)

One interesting fact about the landers is the design of the footpads. Since so little was known about the surface of Mars at that time, it was feared than the Martian surface might be

spongey, and the landers would sink into the surface.[2] For this reason, large

area footpads were used.

Martin Marietta, a predecessor to today's

Lockheed Martin, designed a

heatshield for entry into the

Martian atmosphere composed of a

cork-

silica composite.[2] How the cork was

sterilized to prevent

contamination of the Martian

biosphere is likely an interesting story in itself.

The landers were also designed to detect signs of

life. As a cautionary tale, one of the

life-detecting experiments registered a

false-positive arising from the extreme

oxidizing nature of the

soil. It's believed that the intense

solar ultraviolet radiation, present at the Martian surface because of its lack of a shielding atmosphere, forms

oxidizing agents.

The Viking Lander 2 ceased functioning on April 11, 1980. The Viking Lander 1 held out a little longer, until November 11, 1982. Not surprisingly, events have been planned to

commemorate the arrival at Mars of Viking Lander 1 forty years ago.[5]

The first color image of Mars, acquired by the Viking Lander 1.

(NASA image.)

![]()

References:

- Percival Lowell, "Mars," Houghton Mifflin (Boston, 1895), 228 pages. Facsimile edition published in 1978 by History of Astronomy Reprints.

- Changing Knowledge of Mars Forever: Viking Lander Celebrates 40 Years of Success, Lockheed Martin, June 2016.

- A Viking history fact sheet, NASA Web Site (PDF file).

- Gallery of Viking images, NASA Web Site.

- Viking at 40 Events, NASA Web Site.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Planetary science; 19th century; Juno spacecraft; Jupiter; New Horizons spacecraft; Pluto; natural satellite; moon; chemical compound; composition; planet; Solar System; cloud; rock; core; Clyde Tombaugh; Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835-1910); scientific literature; publish; map; topography; surface feature; Mars; speculative reason; speculation; Martian canals; extraterrestrial intelligence; intelligent race; water; poles of astronomical bodies; oasis; oases; telescope; optical illusion; Percival Lowell (1855-1916); one-percenter; observatory; Lowell Observatory; Flagstaff, Arizona; observational astronomy; altitude; night; theory; theories; book; criticism; critic; Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913); theory of evolution; natural selection; Charles Darwin; facsimile; musing; Edgar Rice Burroughs; novel; Barsoom; plot; human; John Carter of Mars; captain; Confederate States of America; Confederacy; American Civil War; Deus ex machina; unknown process; A Princess of Mars; Mariner 4; spacecraft; impact crater; cratered; technology; mechanical tape recorder; data transmission; Earth; bit rate; data rate; Memnonia quadrangle; Memnonia Fossae; Dejnev; diameter; NASA; tourism; tourist; roadside attraction; highway; planetary exploration; planetary flyby; Viking Lander 1; image resolution; kilometer; millimeter; sand; Chryse Planitia; Viking lander 2; Utopia Planitia; Viking orbiter; meter; landscape; canyon; volcano; lava field; photograph; sponge; spongey; area; Martin Marietta; Lockheed Martin; heatshield; Martian atmosphere; cork; silicon dioxide; silica; composite material; composite; sterilization; sterilize; contamination; biosphere; organism; life; Viking lander biological experiment; false-positive; oxidizing agent; regolith; soil; Sun; solar; ultraviolet radiation; oxidizing agent; commemorate.