James Cronin (1931-2016)

October 6, 2016

Physicists, perhaps purposely

memorializing the

Greek philosophers who were the first to contemplate the

laws of physics, have had an affinity for using

Greek alphabet letters in their

equations, and

Greek words as descriptors. An early example of this is

George Stoney's naming of the

electron after the Greek word for

electrostatically-charging amber, ηλεκτρον. There's also the famous

Alpher–Bethe–Gamow paper, for which

George Gamow added

Hans Bethe as a co-author with his student,

Ralph Alpher, to make an

alpha-

beta-

gamma paper.[1]

A quotation from the first paragraph of Aristotle's Physics. Aristotle (384-322 BC) is depicted to the right of the older Plato (c.425-c.348 BC) in this portion of Raphael's 1509 "The School of Athens" (Left image and Greek text, via Wikimedia Commons. English translation from ref. 2.)[2])

This

predilection is most apparent in the names of many of the

elementary particles. As shown below, seventeen of the twenty four letters of the

classical Greek alphabet have been used.[3]

One elementary particle that's not in this list is the

kaon, also called the K meson. The kaon proved to be an important particle, since the

decay of

neutral kaons

violates CP symmetry. CP symmetry essentially states that physics should be the same when

time is reversed; that is, by playing the "video" of

nature backwards.

The important aspect of this CP violation is that it allows the existence of more

matter than

antimatter in our

universe. For their 1964 discovery of CP violation in neutral kaon decay,

James Cronin (1931-2016) and

Val Fitch (1923-2015) were awarded the 1980

Nobel Prize in Physics. James Cronin died on August 25, 2016, at age 84.[4-7]

James Cronin was born in

Chicago on September 29, 1931, to a father, James Farley Cronin, who was a

graduate student at the

The University of Chicago. His father was a student of

classical languages who had met his future

wife, Dorothy Watson, in a

Greek class at

Northwestern University.[4,7]

In September, 1939, his father became a

professor of

Latin and Greek at

Southern Methodist University in

Dallas, Texas, where Cronin received his

undergraduate education in physics and

mathematics.[6-7] Cronin wrote that a

high school physics teacher inspired his interest in physics.[7]

After receiving his

B.S. degree from Southern Methodist University in 1951, Cronin went to the University of Chicago, where his graduate education involved such professors as

Enrico Fermi and

Murray Gell-Mann.[6] His

thesis under

Samuel Allison was in

experimental nuclear physics on the

spin and

parity of the nuclear states of

carbon.[5-6] He came away from Chicago with an

M.S. (1953), a

Ph.D. (1955), and a wife, Annette Martin, who was also a student at Chicago.[4-5] He was a

National Science Foundation fellow from 1952-1955.[7]

Cronin had a short stay at

Brookhaven National Laboratory (1955-1958), and then became a professor at

Princeton University, staying there until 1971.[7] He finished his career as University Professor of Physics at the University of Chicago.[4] His return to Chicago was prompted by the proximity of the

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) with its 400

GeV particle accelerator.[5,7]

Cronin and Fitch were both Princeton professors when they did their kaon experiment at the Brookhaven National Laboratory

Alternating Gradient Synchrotron accelerator.[4,6] In their 1964

experiments, they found that the long-lived neutral kaon decayed into two pions, an unexpected result that violated CP symmetry.[5] Kaons are interesting, since they

oscillate between normal kaons and antimatter kaons.[6] Cronin and Fitch discovered that the transition from kaon to anti-kaon occurred slightly less frequently.[6]

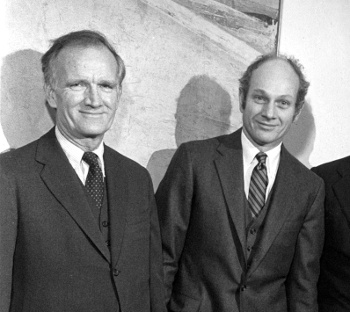

James Cronin, right, with Val Fitch.

Cronin and Fitch were awarded the 1980 Nobel Prize in Physics "for the discovery of violations of fundamental symmetry principles in the decay of neutral K-mesons."

(US Department of Energy photo via Wikimedia Commons.)

Since the effect was small, there was initial

skepticism of the result, but confirming experiments in other

laboratories showed that the effect was real.[6] This experiment showed why a

Big Bang universe could contain just normal matter, and not a mixture of matter and antimatter. Antimatter would decay slightly faster, leaving just normal matter behind.[6]

Cronin was named head of the Fermilab Colliding Beams Division in 1977, a position he held for just a few months before he realized that he enjoyed being a

scientist, not an

administrator.[5] In 1982, he measured the pion lifetime at

CERN.[5] After that, the age of small particle physics experiments was over, the field becoming dominated by huge research teams, and Cronin migrated to

cosmic ray studies.[5]

Cronin helped to start the

Pierre Auger Project, an international

collaboration to investigate cosmic rays and their sources.[4,6] This project sited an array of more than a thousand cosmic ray

detectors covering 3,000

square kilometers in

Argentina to create the

Auger Observatory.[4,5] The James Cronin School, a high school in Malargüe, Argentina, was established through donations by Cronin and private donors.[5]

Cronin was a member of the

American Physical Society, the

National Academy of Sciences, a foreign member of the

Royal Society of London and the

French Legion d'honneur.[4] He was awarded the

National Medal of Science in 1999, the

Ernest Orlando Lawrence Memorial Award for outstanding contributions in the field of

atomic energy in 1977, and the

John Price Wetherill Medal of the

Franklin Institute in 1975.[4]

Edward Kolb,

Dean of the

Physical Sciences Division of the University of Chicago, said this or Cronin:

"Just like in basketball, there are good players in science, but the greatest players are the ones who make the people around them better. Jim was that great player."[4]

Among his survivors are six

grandchildren.[4] One interesting fact is that Cronin did his own

data analysis using

fortran, called FORTRAN in those early days.[5]

References:

- R. A. Alpher, H. Bethe, and G. Gamow, "The Origin of Chemical Elements," Phys. Rev. vol. 73, no. 7 (April 1, 1948), pp. 803f.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.73.803.

- Aristotle, "Physics," R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye, Trans., on the Internet Classics Archive by Daniel C. Stevenson. Also at greek-texts.com.

- There are Greek letters other than these twenty four. One example is the digamma (ϝ), pronounced as waw, or wau, and used as the /w/ sound. Its most common use was as the numeral, six, where it was often written as a final sigma character, ς.

- Steve Koppes, "James W. Cronin, Nobel laureate and pioneering physicist, 1931-2016," University of Chicago Press Release, August 27, 2016.

- Alan Watson, "Obituary - James Cronin (1931–2016), Nature, vol. 537, no. 7621 (September 21, 2016), p. 489, doi:10.1038/537489a.

- James Cronin, Nobel Prize winner in Physics – obituary, Telegraph (UK), August 30, 2016.

- James Cronin - Biographical, From Les Prix Nobel, The Nobel Prizes 1980, Wilhelm Odelberg, Ed., (Nobel Foundation, Stockholm, 1981).

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Physicist; memorialization">memorializing; Ancient Greek philosophy; Greek philosopher; physical law; laws of physics; Greek alphabet letter; equation; Greek language; Greek word; George Stoney; electron; electrostatics; electrostatically-charging; amber; Alpher–Bethe–Gamow paper; George Gamow; Hans Bethe; Ralph Alpher; alpha; beta; gamma; quotation; Aristotle (384-322 BC); Aristotle's Physics; Plato (c.425-c.348 BC); Raphael; The School of Athens; Wikimedia Commons; English language; translation; predilection; elementary particle; classical Greek alphabet; Alpha particle; Rho meson; Beta particle; Sigma baryon; Gamma ray; Tau lepton; Delta baryon; Upsilon meson; Eta meson; Phi meson; Theta meson; Xi baryon; Lambda baryon; J/psi meson; Muon; Omega baryon; Pi meson (Pion); kaon; radioactive decay; electric charge; neutral; CP violation; time; nature; matter; antimatter; universe; James Cronin (1931-2016); Val Fitch (1923-2015); Nobel Prize in Physics; Chicago; postgraduate education; graduate student; The University of Chicago; classical language; wife; Greek language; Northwestern University; professor; Latin; Southern Methodist University; Dallas, Texas; undergraduate education; mathematics; high school; Bachelor of Science; B.S. degree; Enrico Fermi; Murray Gell-Mann; thesis; Samuel Allison; experiment; experimental; nuclear physics; spin; parity; carbon; Master of Science; M.S.; Doctor of Philosophy; Ph.D.; National Science Foundation; fellow; Brookhaven National Laboratory; Princeton University; Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab); electronvolt; GeV; particle accelerator; Alternating Gradient Synchrotron; experiment; neutral particle oscillation; oscillate; Nobel Prize in Physics; US Department of Energy; skepticism; laboratory; Big Bang universe; scientist; administrator; CERN; cosmic ray; Pierre Auger Project; collaboration; photodetector; detector; square kilometer; Argentina; Pierre Auger Observatory; American Physical Society; National Academy of Sciences; Royal Society of London; France; French; Legion d'honneur; National Medal of Science; Ernest Orlando Lawrence Memorial Award; nuclear power; atomic energy; John Price Wetherill Medal; Franklin Institute; Edward Kolb; Dean; Physical Sciences Division of the University of Chicago; basketball; grandchild; data analysis; fortran; R. A. Alpher, H. Bethe, and G. Gamow, "The Origin of Chemical Elements," Phys. Rev. vol. 73, no. 7 (April 1, 1948), pp. 803f.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.73.803.