Whiter Whites

September 5, 2014

Some people prefer to see the world as

black and

white, but the

reality is that nothing is that certain.

Scientifically, pure black and pure white are

technologically useful, but they are difficult to obtain. I wrote about various aspects of white and black in some previous articles (

Thin and Black, August 2, 2013,

Paint it Black, February 13, 2013,

Very White and Very Black, November 23, 2011, and

White Roofs, March 19, 2012).

One measure of the whiteness of an object is its

diffuse reflectivity, known also as

albedo (from the Latin,

alba, "white"). Albedo is the

ratio of

reflected to

incident light, but it's defined at each

wavelength of light. What this means is that something that's black at

visible wavelengths might be white at other wavelengths. The purest white has an albedo of one, and the purest black has an albedo of zero.

Uncooked, polished, white jasmine rice from Thailand.

The characteristic aroma of white jasmine rice comes from 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline (C6H9NO).

(Photograph by Takeaway, via Wikimedia Commons.)

The

natural world has a wide range of albedo. The expression, "

pure as the driven snow," is a

misnomer, since fresh

snow has an albedo of only 0.85. Fresh

asphalt, however, is fairly close to pure black, having an albedo of just 0.02. The albedo of the

Moon is about 0.135.

Two technologically useful white materials are

barium sulfate, which has an albedo of better than 97% at visible wavelengths, and

Teflon (PTFE), with an albedo better than 98%.

Coatings of these materials are used as diffuse reflectors on the inside surface of

integrating spheres for

photometric and

radiometric measurements.

Obtaining a good black poses a problem, since the surface of any

material with a

refractive index n different from

air (n=1) will necessarily reflect light according to the

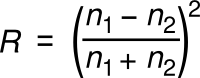

reflectance equation,

where

n1 and

n2 are the refractive indices of air and your material (in any order).

Glass, for example, gives a reflectance

R of about 4% at

normal incidence, so a black glass is still just 96% black.

The solution to the reflectance problem is to have a textured

surface in which incident light is multiply scattered from low reflectance surfaces before it's returned. One black material that incorporates texture to produce a better black is

black gold, which is formed when

gold is

evaporated under an

argon or

nitrogen pressure of about 750

millitorr. Under these conditions, the gold

atoms cool and cluster before attaching to a

substrate, forming a black layer.[1-2] The process works for other

metals, as well.[3]

Before the discovery of

graphene,

carbon nanotubes were the darlings of

materials science, and these offer a means of building highly textured black surfaces.

Scientists from

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute grew arrays of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes to create a super-black material that reflected just 99.955% of incident light at visible wavelengths.[4-5]

Japanese scientists created similar arrays in 2009 to produce a broadband black absorber operable from 0.2 - 200

μm.[6] Similar

research has been pursued by

NASA.[7]

As you look at the world around you, there are a few things, such as some

flower petals, that are colored white. One unusual example of a

natural white is the coloring of the

Cyphochilus beetle, sometimes called the "ghost beetle." The high albedo of this

genus of beetle arises from the texture of its

scales. The properties of these scales has been elucidated by an international team of scientists from the

Università di Firenze (Firenze, Italy),

Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts), the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts),

Exeter University (Exeter, UK), and

Cambridge University (Cambridge, UK).[8-9]

Cyphochilus beetle. (left image and right image by Lorenzo Cortese and Silvia Vignolini, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.)

A white surface will arise from

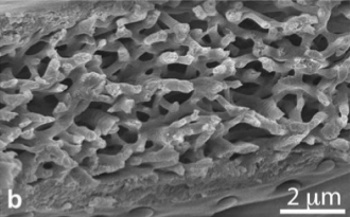

random scattering centers of high refractive index in a thick layer.[8] These scattering centers must reflect all wavelengths of light equally, at least in the visible light spectrum.[9] The Cyphochilus beetles appear white because of an

anisotropic network of

chitin filaments that comprise their scales.[9]

These chitin filaments are extremely thin, too thin to reflect light very well on their own. In the beetle scales, however, their tight

packing allows an efficient scattering of light, and the anisotropy of the packing produces the white color.[8-9] The multiple scattering has the lowest

transport mean free path of any low-refractive-index system discovered to date.[8]

Scanning electron micrograph of the cross-section of the scales of the Cyphochilus beetle.

(Fig. 1b of ref. 8, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.[8]

Says research team leader,

Silvia Vignolini, of the

Cavendish Laboratory,

"Current technology is not able to produce a coating as white as these beetles can in such a thin layer... In order to survive, these beetles need to optimize their optical response but this comes with the strong constraint of using as little material as possible in order to save energy and to keep the scales light enough in order to fly. Curiously, these beetles succeed in this task using chitin, which has a relatively low refractive index."[9]

A random collection of scattering centers by themselves wouldn't give rise to such an intense white as with the chitin material. It's the particular arrangement of the filaments that allows this, and this high-brightness white comes from a material with a low

mass per unit

area.[8-9] The

artificial production of such structures would have many applications, such as making whiter

paper,

plastics and

paints.[8] Says Vignolini,

"The lessons we are learning from these beetles is two-fold... On one hand, we now know how to look to improve scattering strength of a given structure by varying its geometry. On the other hand the use of strongly scattering materials, such as the particles commonly used for white paint, is not mandatory to achieve an ultra-white coating."[8]

The

research was funded by the

European Research Council and the

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.[8]

References:

- John Lehman, Evangelos Theocharous, George Eppeldauer and Chris Pannell, "Gold-black coatings for freestanding pyroelectric detectors," Measurement Science and Technology, vol. 14, no. 7 (July, 2003).

- W. Becker, R. Fettig and W. Ruppel, "Optical and electrical properties of black gold layers in the far infrared," Infrared Physics & Technology, vol. 40, no. 6 (December, 1999), pp. 431-445.

- Chih-Ming Wang, Ying-Chung Chen, Maw-Shung Lee and Kun-Jer Chen, "Microstructure and Absorption Property of Silver-Black Coatings," Jap. J. Appl. Phys. vol. 39, Part 1, no. 2A, (February 15, 2000) pp. 551-554.

- Zu-Po Yang, Lijie Ci, James A. Bur, Shawn-Yu Lin and Pulickel M. Ajayan, "Experimental Observation of an Extremely Dark Material Made By a Low-Density Nanotube Array," Nano Lett., vol. 8, no. 2 (February, 2008), pp 446-451.

- Researchers Develop Darkest Man-Made Material, Inside Rensselaer, vol. 2, no. 2, January 31, 2008.

- Kohei Mizuno, Juntaro Ishii, Hideo Kishida, Yuhei Hayamizu, Satoshi Yasuda, Don N. Futaba, Motoo Yumura and Kenji Hata, "A black body absorber from vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes," Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 106, no. 15 (April 14, 2009), pp. 6044-6047.

- Lori Keesey and Ed Campion, "NASA Develops Super-Black Material That Absorbs Light Across Multiple Wavelength Bands," NASA Goddard Press Release No. 11-070, November 8, 2011.

- Matteo Burresi, Lorenzo Cortese, Lorenzo Pattelli, Mathias Kolle, Peter Vukusic, Diederik S. Wiersma, Ullrich Steiner, and Silvia Vignolini, "Bright-White Beetle Scales Optimise Multiple Scattering of Light," Scientific Reports, vol. 4, article no. 6075 (August 15, 2014), doi:10.1038/srep06075. This is an open access article with a pdf file, here.

- The beetle's white album, University of Cambridge Press Release, August 15, 2014.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Black; white; reality; science; scientific; technology; technological; diffuse reflection; diffuse reflectivity; albedo; ratio; reflection; reflected; incident; light; wavelength; visible wavelength; jasmine rice; Thailand; 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline; Wikimedia Commons; nature; natural world; pure as the driven snow; misnomer; snow; asphalt; Moon; barium sulfate; polytetrafluoroethylene; Teflon; coating; integrating sphere; photometry; photometric; radiometry; radiometric; material; refractive index; atmosphere of Earth; air; reflectivity; reflectance; glass; angle of incidence; normal incidence; surface; gold; evaporation; evaporate; argon; nitrogen; pressure; torr; atom; substrate; metal; graphene; carbon nanotube; materials science; scientist; Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute; Japan; Japanese; micrometer; μm; research; NASA; flower; petal; nature; natural; Cyphochilus; beetle; genus; scale; Università di Firenze (Firenze, Italy); Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts); Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts); Exeter University (Exeter, UK); Cambridge University (Cambridge, UK); Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License; randomness; random; anisotropy; anisotropic; chitin; relative density; packing; transport mean free path; Silvia Vignolini; Cavendish Laboratory; optics; optical; energy; mass; flight dynamics; area; artificial; paper; plastic; paint; geometry; European Research Council; Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.