Distinguishing Smells

April 2, 2014

Smell (more properly,

olfaction) is one of our five

senses, and it surely exists as an

evolutionary advantage we share with other

animals. One purpose of smell is to distinguish between good

foods and those that are spoiled or not that

nutritious.

One other purpose of smell is as an aid in finding a

mate. Animals emit complex

chemical vapors called

pheromones to signal their presence. Since pheromone sense is not as developed in humans as in animals, we augment

our own odor with

perfume and

cologne. These work, since I still associate certain perfume scents with past

girlfriends. I wrote about some aspects of our sense of smell in a

previous article (Smell, October 23, 2013).

Early

chemists would identify some

chemicals, such as

sulfites, by the

odor they emitted when

heated. They would also use

taste to identify chemicals. Accidental tasting of chemical residue on his hand is how

Constantin Fahlberg discovered

saccharin in 1878. Tasting your chemicals is now a prohibited practice.

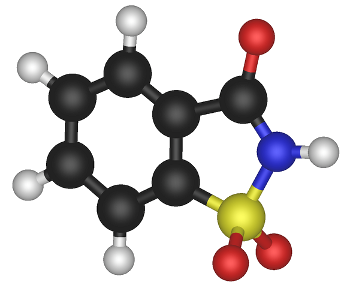

A saccharin molecule.

Carbon atoms are black; hydrogen, white; oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; and sulfur, yellow,

(Illustration by Michael Ströck, via Wikimedia Commons.)

The perception of odor was merely

qualitative throughout most of

human history until it was realized that what we smell is a direct consequence of the mixture of chemicals arriving at our

nose.

Gas chromatography is a method of analysis of volatile chemicals; and, combined with a

mass spectrometer, it will identify precisely which chemicals produce a specific odor. It will also identify an odor without human presence.

In the real world, it's not possible to carry a

cubic meter of equipment with us for the

chemical analysis of odors, such as those from

spoiled food, so scientists have been developing

electronic noses. Electronic noses work by either

charge or

mass detection.

In the former case, odorant

molecules adsorbed on a

selective receptor layer direct charge to a

metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor or a

conducting polymer layer. In the later case, the added mass of the adsorbed molecules is detected by a

quartz crystal microbalances or a

surface acoustic wave device.

Although the sense of smell is well developed in many animals, humans can readily distinguish subtle differences in odors, and the number of

fragrances for sale in a

department store perfume section will attest. How many different odors are identifiable to a human? That's the question that a team of

scientists from

The Rockefeller University (New York, NY) and the

Howard Hughes Medical Institute (New York, NY) addressed in a recent study published in the

journal,

Science.[1] The surprising answer is more than a

trillion.[1-5]

Chanel No. 5

This iconic fragrance was created by Russian perfume chemist, Ernest Beaux.

Beaux innovated by using aldehydes in the fragrance mixture.

Although you wouldn't put formaldehyde in a fragrance, other aldehydes such as lemon-scented citronellal work well.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Of course, such a study involves

human subjects, and these were presented with mixtures of 10, 20, or 30 components from a

library of 128 chemical compounds. Based on an analysis of the collected data, it appears that a trillion might be a lower limit of the human capacity to distinguish different odors.[1] This capability far outweighs our capacity for recognizing

colors (2.3 - 7.5 million), and different

tones (about 340,000); and it is a far stretch from a

1920s estimate that humans can discriminate between 10,000 odors.[1-3,5]

The odors that we perceive in our

environment don't arise from a single chemical. They're a mixture of many. The scent of a

rose has 275 chemical components, although a few of these dominate.[3,5] To simulate the odor spectrum, the research team used 128 chemical, such as those with scents like

citrus,

mint,

tobacco,

garlic, but they created mixtures that had unfamiliar odors. They were neutral odors that were neither very pleasant nor very unpleasant.[3]

In the

experiments, twenty-six test subjects, aged 20-48, were presented with three

vials of chemicals at a time, two of which were identical. They were asked to choose the odd vial, and they did this in 264 trials each. When the numbers of chemical components overlapped by more than 51%, the test subjects had difficulty discriminating the scents. This allowed an estimate of how many unique scents could be identified if the test subjects were presented with all possible mixes of the 128 odor molecules.[2-3,5]

We have the capability to distinguish so many distinct odors because the human nose has about 400 types of scent

receptors, and these outperform the other senses in discriminating between

stimuli.[1-3] Says study coauthor,

Andreas Keller, "My hope is that this helps to dispel the myth that humans have a bad sense of smell."[2] However, our olfactory sense is still far behind that of

dogs, whose sense of smell is 1,000-10,000 times more sensitive.[5]

"Take Yourself by the Nose"

This 17th century oil on wood painting expresses the German proverb, "Nimm dich selbst bei der Nase."

This is also known as the "Bird of Self-Knowledge."

(Photo by Javier Carro, via Wikimedia Commons.)

![]()

References:

- C. Bushdid, M. O. Magnasco, L. B. Vosshall and A. Keller, "Humans Can Discriminate More than 1 Trillion Olfactory Stimuli,", Science, vol. 343, no. 6177 (March 21, 2014), pp. 1370-1372.

- Jessica Morrison, "Human nose can detect 1 trillion odours," Nature News, March 20, 2014.

- Will Dunham, "Sweet smell of success: human nose discerns giant array of odors," Reuters, March 20, 2014.

- Joseph Stromberg, "The Human Nose Can Distinguish Between One Trillion Different Smells," Smithsonian Magazine, March 21, 2014.

- Sniff study suggests humans can distinguish more than 1 trillion scents, Rockefeller University Press Release, March 20, 2014.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Smell; olfaction; sense; evolutionary advantage; animal; food; nutrition; nutritious; marriage; mate; chemical compound; vapor; pheromone; body odor; perfume; cologne; girlfriend; chemist; sulfite; odor; heat; taste; Constantin Fahlberg; saccharin; carbon; hydrogen; oxygen; nitrogen; sulfur; Wikimedia Commons; qualitative property; human history; nose; gas chromatography; mass spectrometry; mass spectrometer; cubic meter; analytical chemistry; chemical analysis; food spoilage; electronic nose; electric charge; mass; molecule; adsorption; adsorbed; olfactory receptor; metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor; conductive polymer; conducting polymer; quartz crystal microbalances; surface acoustic wave device; aroma compound; fragrance; department store; scientist; The Rockefeller University (New York, NY); Howard Hughes Medical Institute (New York, NY); scientific journal; Science; trillion; Chanel No. 5; Russian; Ernest Beaux; aldehyde; formaldehyde; citronellal; human subject research; human subject; chemical library; color; pitch; tone; 1920s; environment; rose; citrus; mint; tobacco; garlic; experiment; vial; sensory receptor; stimulus; Andreas Keller; dog; 17th century; oil on wood painting; German; proverb.