Kenneth G. Wilson

June 21, 2013

Wilson is a common

English surname. It's a

patronymic form, meaning the "son of Will," and Will was historically a very common English name. In that sense, it's the same as the

Russian "-ovich," and the

Hebrew "bar-." Wilson is the seventh most common surname in the

United Kingdom, and it's the eighth most common surname in the

United States.

Although the name, Wilson, is common,

physics has been graced by many uncommon

physicists having the name Wilson. Here are a few of the most prominent, arranged

chronologically by birth date.

•

Charles Thomson Rees Wilson (1869-1959) received the 1927

Nobel Prize in Physics for the

invention of the

cloud chamber at

Cambridge University. One of his

academic mentors was

J. J. Thomson, winner of the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the

electron.

•

William Wilson (1887-1948) worked with

Rutherford on

radioactivity, and he joined

Bell Labs in 1915 to work on

radiotelephone systems. He was awarded the

IEEE Medal of Honor in 1943 for his radiotelephone research.

•

Alan Herries Wilson (1906-1995) was a

mathematical physicist who studied

quantum mechanics under

R.H. Fowler and

Werner Heisenberg. In physics, he is best known for formulating the

energy band theory of

electrical conductance. Elsewhere, he is known as

chairman of the

pharmaceutical company,

Glaxo, from 1963 until retirement in 1973. Physicists are very capable managers, as many government and industrial organizations have found.

•

Olin Chaddock Wilson (1909-1994) was an American

astronomer who worked on

stellar spectroscopy. He discovered

stellar activity cycles, the stellar equivalent of our

Sun's sunspot cycle.

•

Robert Rathbun Wilson (1914-2000) was director of the

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) from 1967–1978. During

World War II, he was a

group leader for the

Manhattan Project.

•

Richard Wilson (1926-). Richard Wilson is an

emeritus professor of physics at

Harvard University. He has

authored nearly a thousand scientific papers and articles in

particle physics and

nuclear risk assessment.

•

Robert Wilson (1927-2002) was an astronomer who was leader of the first all sky survey in the

ultraviolet by the

European Space Research Organization's TD-1A astronomy satellite in 1972. He was the principal proponent of the

International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) satellite, a collaboration between

NASA,

ESA and the

UK.

•

Herbert R. Wilson (1929-2008) worked under the direction of

John Randall at

King's College London, on the structure of

DNA.

•

Robert Woodrow Wilson (1936-) Shared the 1978 Nobel Prize

in Physics for his discovery, with

Arno Allan Penzias, of the

cosmic microwave background radiation.

•

Kenneth Geddes Wilson (June 8, 1936 - June 15, 2013) was the recipient of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physics. Read more about Kenneth Wilson, about whom this article is written, below.

Kenneth Wilson (left) with fellow Nobel Laureate, Hans Bethe, and Cornell University colleagues celebrating his award of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physics, October 1982.

(Photograph from the Cornell University Carl A. Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, used with permission.)

•

Raymond N. Wilson developed the concept of

active optics, which is the operating principle of today's

large diameter telescopes and

segmented-mirror telescopes.

American

theoretical physicist,

Kenneth Geddes Wilson, who died last Saturday, June 15, 2013, was the sole recipient of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physics.[1-4] Wilson, who was a resident of

Gray, Maine, died from complications of

lymphoma in

Saco, Maine, at age 77.[3] His Nobel Prize was given "for his theory for critical phenomena in connection with phase transitions."[5] His particular achievement was to apply the concept of the

renormalization group to

phase transitions, which explained also the confinement of

quarks inside

hadrons.

Kenneth Geddes Wilson was born in

Waltham, Massachusetts, on June 8, 1936, to

Harvard University chemist,

Edgar Bright Wilson, and Emily Buckingham Wilson, who had done

graduate work in physics before her

marriage.[1,3] His father bought him books on physics and

mathematics, and he skipped several grades in school. Wilson said that

high school was "dull," and he would pass the time waiting for his

school bus by doing

cube roots.[3]

Attending Harvard as an

undergraduate, he excelled at both

sports and mathematics. He scored twice among the top five in the annual

Putnam mathematics competition, in 1954 and 1956.[1,3] As a Junior Fellow, he proved a mathematical conjecture proposed by

Freeman Dyson.[1] Graduating from Harvard in 1956, Wilson decided to pursue physics, rather than mathematics, deciding that "It was connected to the real world."[3] He was awarded his

Ph.D. from

Caltech in 1961, having studied under Physics Nobelist,

Murray Gell-Mann.[2-3]

After getting his Ph.D., Wilson went directly to

CERN, but two years later he was recruited by the

Cornell University physics department. [3] Interestingly, one of the inducements for going to Cornell, as he stated in his

Nobel Foundation biography, was its

folk dancing group. Wilson had taken up folk dancing as a

hobby in

graduate school.[3] Although it's typically a "

publish or perish" world in academia, he received

tenure shortly thereafter, although he had hardly published. His chosen specialty,

quantum field theory, did not lead to quick publications.[1-2] Prominent among his doctoral students at Cornell were

Roman Jackiw, and

Paul Ginsparg, whom I wrote about in a

previous article (ArXiv at Twenty, August 24, 2011).

Wilson's Nobel Prize research involved phase transitions. Simple such transitions as

boiling are known to everyone, but the physics at the transition point, called the

critical point, are complicated.[4] Wilson cracked the critical point problem by looking at fluctuations over a wide range of length scales, proving that these transitions are a phenomenon that involves the substance as a whole, not just the local

molecular environment. This was shown to be a

universal feature of phase transitions.[4] Wilson showed that this complex problem could be broken into smaller calculations using

renormalization group theory.[4]

In another leap of physics, Wilson decided that this approach would work beyond molecules and would apply, also, to the

elementary particles he had studied as a graduate student. He developed a theory of

quantum chromodynamics on a

space-time lattice, and this allowed calculation of the

strong forces that bind

quarks into

hadrons.[1-2] Such calculations require significant

computing, so Wilson championed the formation of the

NSF supercomputer centers, one of which was placed at Cornell.[1-2] Wilson was named the first director of the Cornell supercomputer center in 1985.

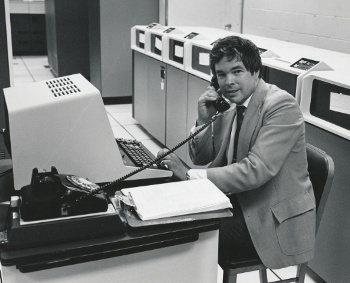

Life among the bits.

Note the juxtaposition of the rotary dial telephone and the advanced computing equipment.

(Photograph from the Cornell University Carl A. Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, used with permission.)

Paul Ginsparg, a professor of physics and

information science at Cornell and one of Wilson's doctoral students, says that Wilson "...was decades ahead of his time with respect to computing and networks..."[2] Ginsparg said that Wilson would write code for calculating on

parallel arrays of processors to overcome the limitations of slow, individal processors. He also saw the importance of

computer networking. Ginsparg, as quoted in

Physics World, says, "As a graduate student in the late 1970s, I had a unique three-decade window into the future."[4]

In 1988, Wilson became a faculty member at

Ohio State University, where he was actively involved in improving

education. While at Ohio State, he helped found the

Physics Education Research Group.[1,2] He was

co-principal investigator of an NSF educational reform project called "

Project Discovery." This was an attempt at development of

inquiry-based learning of physics in schools.[4]

In 1994, Wilson co-authored a book with Bennett Daviss, entitled, "Redesigning Education."[6] Said Wilson,

"The current crisis in education is costing us the American Dream... We must make a quantum change in our concept of education itself if our society and culture are to survive intact in the new century."[1]

Along with the Nobel Prize in Physics, Wilson was awarded the 1980

Wolf Prize in Physics, and he received an honorary doctorate of science from his undergraduate

alma mater, Harvard, in 1981.[1,2] He was elected to the

National Academy of Sciences and the the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, in 1975; and the

American Philosophical Society, in 1984.[4] Physics Nobelist,

Steven Weinberg, had this praise for Wilson,

"Ken Wilson was one of a very small number of physicists who changed the way we all think, not just about specific phenomena, but about a vast range of different phenomena."[1-2]

Aside from his love of folk dancing, Wilson skied, and he was an avid

hiker. He had an informal

demeanor, and he was comfortable in the company of students.[1] Wilson's survivors include his wife, Alison Brown, and his brother,

David Wilson, who is a professor in Cornell's

Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics.[1-3]

Wilson was once asked in an interview how he got interested in computing.

He replied that it was his "utter astonishment at the capabilities of the Hewlett-Packard pocket calculator... I buy this thing and I can't take my eyes off it, and I have to figure out something that I can actually do that would somehow enable me to have fun with this calculator."[3]

(Photo of author's HP-33C Programmable Calculator)

![]()

References:

- Syl Kacapyr, "Pioneering physicist and Nobel Laureate Kenneth Wilson dies," Cornell University Press Release, June 17, 2013.

- Physics Nobel laureate Kenneth Wilson dies, Cornell University News, June, 18, 2013.

- Martin Weil, "Kenneth Wilson, Nobel winner who explained nature's sudden shifts, dies in Maine at 77," Bangor Daily News, June 19, 2013.

- Michael Banks, "Physicist Kenneth Wilson dies at 77," Physics World, June 18, 2013.

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 1982 - Kenneth G. Wilson, Nobel Prize Web Site.

- Kenneth G. Wilson and Bennett Daviss, "Redesigning Education," Teachers College Press (August 1, 1996), 254 pages, ISBN-13: 978-0807735855 (via Amazon).

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Wilson; English language; surname; patronymic; Russian language; Jewish name; Hebrew; United Kingdom; United States; physics; physicist; chronology; chronological; Charles Thomson Rees Wilson (1869-1959); Nobel Prize in Physics; invention; cloud chamber; University of Cambridge; Cambridge University; academia; academic; mentor; J. J. Thomson; electron; William Wilson (1887-1948); Ernest Rutherford; radioactive decay; radioactivity; Bell Labs; radiotelephone; IEEE Medal of Honor; Alan Herries Wilson (1906-1995); mathematical physicist; quantum mechanics; Ralph H. Fowler; Werner Heisenberg; electronic band structure; energy band theory; electrical conductance; chairman; pharmaceutical company; Glaxo; Olin Chaddock Wilson (1909-1994); astronomer; stellar spectroscopy; star; stellar; Sun; sunspot cycle; Robert Rathbun Wilson (1914-2000); Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab); World War II; group leader; Manhattan Project; Richard Wilson (1926-); emeritus professor; Harvard University; scientific papers and articles; particle physics; nuclear weapon; risk assessment; Robert Wilson (1927-2002); ultraviolet; European Space Research Organization; TD-1A astronomy satellite; International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) satellite; NASA; European Space Agency; ESA; United Kingdom; UK; Herbert R. Wilson (1929-2008); John Randall; King's College London; DNA; Robert Woodrow Wilson (1936-); Arno Allan Penzias; cosmic microwave background radiation; Kenneth Geddes Wilson (June 8, 1936 - June 15, 2013); Hans Bethe; Cornell University; Cornell University Carl A. Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections; Raymond N. Wilson; active optics; large diameter telescope; segmented-mirror telescope; theoretical physics; theoretical physicist; Kenneth Geddes Wilson; Gray, Maine; lymphoma; Saco, Maine; renormalization group; phase transition; quark; hadron; Waltham, Massachusetts; Harvard University; chemist; Edgar Bright Wilson; graduate school; marriage; mathematics; Secondary education in the United States; high school; school bus; cube root; undergraduate; sports; William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition; Putnam mathematics competition; Freeman Dyson; Doctor of Philosophy; Ph.D.; California Institute of Technology; Caltech; Murray Gell-Mann; CERN; Cornell University; physics department; Nobel Foundation; folk dancing; hobby; publish or perish; tenure; quantum field theory; Roman Jackiw; Paul Ginsparg; boiling; critical point; molecule; molecular; universality in dynamical systems; renormalization group theory; elementary particle; quantum chromodynamics; space-time; lattice; strong interaction; strong force; computing; National Science Foundation; NSF; supercomputer; rotary dial; telephone; information science; parallel computing; parallel arrays of processors; National Science Foundation Network; computer networking; Physics World; Ohio State University; education; Physics Education Research Group; principal investigator; Project Discovery; inquiry-based learning; Wolf Prize in Physics; alma mater; hiking; hiker; demeanor; David Wilson; Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics; Hewlett-Packard pocket calculator; Kenneth G. Wilson and Bennett Daviss, "Redesigning Education," Teachers College Press (August 1, 1996), 254 pages, ISBN-13: 978-0807735855.