Nickel-Copper Nanowires

June 5, 2012

The well-known formula for the

electrical resistance R of a

wire contains a lot of useful information; viz.,

R = ρL/A

where

ρ is the material

resistivity, measured in

ohm-

meters,

L is the length of the wire, and

A is its

cross-sectional area. A low resistance wire, which is what's needed in most applications, will be made from a low resistivity (high

conductivity) material, will have a large cross-sectional area, and will be as short as possible.

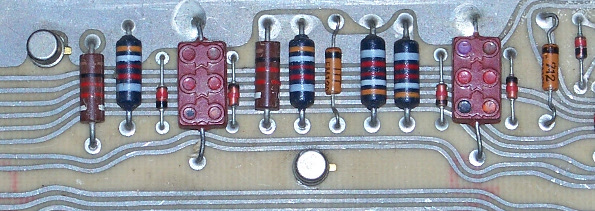

Sometimes, your object is a high resistance, as provided by these resistors on a circuit board from a Univac 9200 Computer (c. 1966). Also shown are diodes (regular and zener), transistors (round objects), and some antique capacitors (rectangular objects). (Photo by the author.)

The wiring that concerns most people is the wiring in the walls of their house. In the US, these

copper wires are usually 12 or 14

AWG (American Wire Gauge). What's confusing to most people, but not to

machinists, is that lower gauge numbers are for thicker wires. Some properties of these wires are listed in the table, below.

| AWG | dia. (mm) | dia. (inch) | mΩ/m | mΩ/foot |

| 12 | 2.053 | 0.0808 | 5.211 | 1.588 |

| 14 | 1.628 | 0.0641 | 8.286 | 2.525 |

The ohms/foot value is significant, since it specifies what the

voltage drop and

resistance heating of the wire will be. For fifteen

amperes, which is about the

current draw of a

hair dryer, a fifty foot run of 14 AWG wire would have a voltage drop of nearly two volts because of its 0.126 ohm resistance. This will generate 28

watts of heat inside the walls of your house. Fortunately, this heat is distributed along the length of the wire, but it's a significant

energy loss (~2% for the hair dryer).

At one time,

aluminum wiring was used for some residential wiring in the US, since it was less expensive than copper and almost as conductive. Aluminum, however, was not quite up to the task for a variety of reasons, the most important of which is

mechanical creep at wire joins and joins of wire to

switches and

receptacles. An originally tight connection can become loose over time, causing a high

contact resistance.

Although copper and aluminum are the best solution for most wiring applications, including conductors on

integrated circuits, they aren't the only high conductivity metals, as the following table shows.

| Electrical Conductors (Data at 20°C from Wikipedia) |

† 18% Cr, 8% Ni

Austenitic

One thing that the table shows is that most

pure elements have lower resistivity than

alloys, a fact that's

easily understood. The high resistivity of alloys works to an advantage in some applications, such as transformer cores, where you want a high resistance to prevent

core losses from

eddy currents.

Silicon steel (47.2 x 10

−8 ohm-meter) is used in

transformer core applications.

Amorphous metals have about three times the resistivity of silicon steel (100-150 x 10

−8 ohm-meter).

Early computers were called "Big Iron" for a reason. There were a lot of transformers, like this, with silicon steel laminated cores. Switched-mode power supplies have made everything lighter.

(Photo by Arnold G. Reinhold, via Wikimedia Commons.)

When we consider

nanowires, we're immediately faced with the reality of a very low cross-sectional area, perhaps mitigated by a small length. The cross-sectional area scales as the

square of the dimension, so it's a major problem. Nonetheless, nanowires have been researched as a way to produce the conductive, yet

transparent,

electrodes required for

displays.

As I wrote in a

previous article (Transparent and Conductive, June 10, 2011),

carbon nanotubes, the wonder material of the decades before

graphene, mixed in a

polymer, have been investigated for such an application by

scientists at the

Eindhoven University of Technology (

Eindhoven,

The Netherlands).[1-2]

Silver nanowires, overcoated with a

conductive polymer, likewise form a good quality transparent electrode.[3-4]

I reviewed the

silver nanowire work by scientists at the

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in

another article (Silver Nanowire Transparent Electrodes

December 19, 2011). The important feature of the UCLA nanowires is that a conductive polymer overcoating of

PEDOT:PSS (poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrenesulfonate)) provides a conductive path between individual nanowires to enhance electrical conductivity.[3-4]

Copper is as conductive as silver, but it's a thousand times more abundant and less expensive; so, copper nanowires are a potential material for this application. Copper nanowires, however, have an

orange color, and they

oxidize when exposed to

air. Recent research at

Duke University has addressed both these problems by putting a

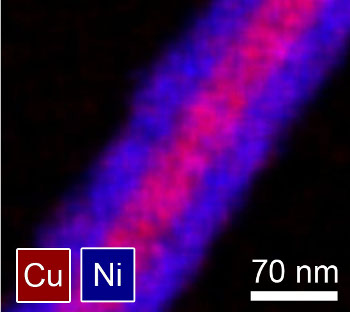

nickel coating over the copper nanowires.[5-6]

Benjamin Wiley, an assistant professor of

chemistry at Duke, and his students examined the

sheet resistance of uncoated copper nanowire films, and they found that it doubles after three months at

room temperature. Silver nanowire films perform better, doubling resistance after three years,[6] but the sheet resistance of copper nanowires, coated with 20

mol-% nickel, will double only after hundreds of years. The Ni-coated wires have a

gray color that's less noticeable in displays.[5]

Image of a nickel-coated copper nanowire.

(Image supplied by Benjamin Wiley, used with permission)

At this point, the conductivity of the nickel-coated copper nanowire films is less than that of

indium-tin oxide (ITO) of the same transparency. However, this nanowire material is promising on many counts, and Wiley has started

NanoForge Corp., a

Durham, North Carolina, startup company, to develop this material.[5]

References:

- Ivo Jongsma, "Researchers find replacement for rare material indium tin oxide," Eindhoven University of Technology Press Release, April 11. 2011.

- Andriy V. Kyrylyuk, Marie Claire Hermant, Tanja Schilling, Bert Klumperman, Cor E. Koning and Paul van der Schoot, "Controlling electrical percolation in multicomponent carbon nanotube dispersions," Nature Nanotechnology (Published online April 10, 2011).

- Jennifer Marcus, "UCLA team develops highly efficient method for creating flexible, transparent electrodes," UCLA Press Release, November 21, 2011.

- Rui Zhu, Choong-Heui Chung, Kitty C. Cha, Wenbing Yang, Yue Bing Zheng, Huanping Zhou, Tze-Bin Song, Chun-Chao Chen, Paul S. Weiss, Gang Li and Yang Yang, "Fused Silver Nanowires with Metal Oxide Nanoparticles and Organic Polymers for Highly Transparent Conductors," ACS Nano (DOI: 10.1021/nn203576v), October 28, 2011.

- Ashley Yeager, "Copper-Nickel Nanowires Could Be Perfect Fit For Printable Electronics," Duke University Press Release, May 29, 2012.

- Aaron R Rathmell, Minh Nguyen, Miaofang Chi and Benjamin John Wiley, "Synthesis of Oxidation-Resistant Cupronickel Nanowires for Transparent Conducting Nanowire Networks," Nano Letters, Just Accepted Manuscript (May 29, 2012), DOI: 10.1021/nl301168r.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Electrical resistance; wire; >resistivity; ohm; meter; cross-sectional area; conductivity; resistor; printed circuit board; circuit board; Univac 9200 Computer; diode; zener; transistor; capacitor; copper; American wire gauge; AWG; machinist; millimeter; mm; inch; meter; foot; voltage; Joule heating; resistance heating; ampere; electric current; hair dryer; watt; energy; aluminum wire; mechanical creep; switch; receptacle; contact resistance; integrated circuit; Wikipedia; silver; iron; copper; platinum; gold; tin; aluminium; 1010 carbon steel; calcium; lead; tungsten; titanium; zinc; stainless steel; nickel; mercury; lithium; nichrome; Austenitic; pure element; alloy; core loss; eddy current; silicon steel; transformer; amorphous metal; Big Iron; Switched-mode power supply; Arnold G. Reinhold; Wikimedia Commons; nanowire; exponentiation; square; transparency; transparent; electrode; display; carbon nanotube; graphene; polymer; scientist; Eindhoven University of Technology; Eindhoven; The Netherlands; silver nanowire; conductive polymer; University of California, Los Angeles; PEDOT:PSS; orange color; oxide; oxidize; air; Duke University; Benjamin Wiley; chemistry; sheet resistance; room temperature; mole; mol-%; gray color; indium-tin oxide; ITO; NanoForge Corp.; Durham, North Carolina.