Trees (Wooden Variety)

July 27, 2011

Galileo (1564-1642) was the first modern

physicist, and his

scientific method is indistinguishable from that of today's experimental physicists.

Mechanics was his primary occupation, and that extended to the

mechanical properties of materials. His dialogue,

Two New Sciences (1638), was concerned with both the motion of objects and the strength of materials.

In Two New Sciences, Galileo expressed what's called the

square-cube law, which, simply stated, is that as an object is proportionally increased in size, it's

volume increases as the cube of the proportion, but its

surface area increases as the square of the proportion.

The idea he expressed was that large objects do not behave as their smaller counterparts. A large building proportioned to a smaller structure will be weaker, and large

animals need proportionately larger bones, among other adaptations. The later principle is something that

science fiction films regularly disobey.[1]

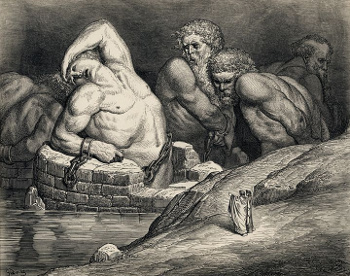

Not a scientifically accurate depiction of large humanoid forms.

Gustave Doré's illustration of titans and giants for Dante's Inferno, Plate LXV, Canto XXXI.

(Via Wikimedia Commons))

As Sagredo, one of the participants in Galileo's discourse, states,[2]

"From what you have said, it appears to me impossible to build two similar structures of the same material, but of different sizes and have them proportionately strong; and if this were so, it would not be possible to find two single poles made of the same wood which shall be alike in strength and resistance but unlike in size."

Trees exist in a wide range of sizes, from foot tall

bonsai to the

Sequoioideae, the tallest of which, the

Sequoia sempervirens, is more than 375 feet high. Such a height requires a 25 foot diameter trunk.

A explained in a

previous article (Synthetic Xylem, September 24, 2008), trees need to obey more than the square-cube law.

suction pumps can't raise

water much more than 30 feet, so how can trees can grow as high as 120

meters, since

water must somehow get to their tops?

The answer is

capillarity. Because of capillarity, water will rise in a tube of inside radius r to an approximate height h given by

h = (1.4 x 10-5)/ r

where h and r are in the same units. A tube of one micrometer radius will raise water to a height of about 14 meters, so water will reach such great heights if there are tube-like structures in a tree of 100

nm dimension; provided, however, that the water column can hold itself together over such a great height. More information on this problem can be found in the references.[3-5]

A team of

scientists from the

Department of Earth Atmosphere and Planetary Sciences,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts), the

Santa Fe Institute (Santa Fe, New Mexico),

Portage, Inc. (Los Alamos, New Mexico), the

Department of Physics and the

Institute for Physical Science and Technology,

University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland) and the

Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, New Jersey) have tried to fold all possible parameters into a model that predicts maximum tree height as a function of environmental conditions across the

continental United States.

Maximal tree heights in the continental US.[7]

There is quite a range of maximal tree heights across the US, as shown in the figure above. Trees of the desert

Southwest are quite small. The

Northeast, where I live, have quite a few tall trees; and, as mentioned above, the sequoias of the

Pacific Northwest are the record holders. The range of maximal size must be related to the environment in which the trees grow, but how?

The

model developed by this research team includes the constraints given by the local resources, such as

rainfall,

humidity,

temperature and

insolation. Extending their findings from the trees to the

forest, they're able to estimate the density of the

leaf canopy, and thereby the canopy

albedo; that is, the reflectance of sunlight. This parameter is important for

climate models.

Not surprisingly, the model uses the mechanical constraints outlined above, including the modeling of the

arboreal vascularia as a

fractal network. Chris Kempes, an author of the study who's a Ph.D. student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, explains the fractal concept this way:[6]

"The branches of a tree really form a fractal, where if you cut off one of the limbs... and blow it up to the size of the tree, it’ll look like the whole tree. If you nail down that network structure correctly, then you can use it to predict how things change with size."

The model is based on an idealized tree described by its internal fluid flow rate and size. This tree is "planted" in an environment of variables such as average temperature, rainfall, humidity and insolation. The model gives good predictions, except for the desert Southwest and parts of

New England. The former can be explained by the extreme environment of the desert; the later, by the extensive

logging that took place in New England in the early history of the US.[6-7] The agreement between

theory and observation can be seen from the figure.[7]

Comparison of tree height model with observations.[7])

Using their model to make predictions of the response of trees to

climate change, the research team found that a 2°C increase in global temperature will reduce the average height of the tallest trees about 11 percent. Cooling by 2°C will increase height by 13%.[6-7]

A study to be published in the

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and recently published online,[8-9] gives credence to the folk wisdom known as "the nursery effect," in which supposedly identical trees raised in different environments have a different environmental response. Tree planting as a method of

carbon sequestration will involve much more than the mechanical act of planting trees, but also more research on trees themselves.

References:

- Michael C. LaBarbera, "The Biology of B-Movie Monsters," The University of Chicago, 2003.

- Galileo Galilei, "Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche intorno a due nuove scienze," 1638.

"E da quanto ella ha detto parmi chedovrebbe seguire che fusse impossibil cosa costruire due fabbriche dell'istessa materia simili e diseguali, e tra di loro con egual proporzione resistenti; e quando ciò sia, sarà anco impossibile trovar due sole aste dell'istesso legno tra di loro simili in robustezza e valore, ma diseguali in grandezza."

- Keay Davidson, "Redwoods: How tall can they grow?" (San Francisco Chronicle Online, April 26, 2004.

- George W. Koch, Stephen C. Sillett, Gregory M. Jennings and Stephen D. Davis, "The limits to tree height," Nature, vol. 428, no. 6985 (April 22, 2004), pp. 851-854.

- George Koch, Stephen Sillett, Gregg Jennings and Stephen Davis, "How Water Climbs to the Top of a 112 Meter-Tall Tree" (Plant Physiology Net).

- Jennifer Chu, "The tallest tree in the land - New model predicts maximum tree height across the United States; gives information about forest density, carbon storage," MIT Press Release, July 18, 2011.

- C.P. Kempes, G.B. West, K. Crowell and M. Girvan M, "Predicting Maximum Tree Heights and Other Traits from Allometric Scaling and Resource Limitations," PLoS ONE, vol 6, no. 6 (June 13, 2011), Document No. e20551.

- Mark Kinver, "Nursery effect study shows trees remember their roots," BBC News, July 12, 2011

- Sherosha Raja, Katharina Bräutigama, Erin T. Hamanishib, Olivia Wilkinsa, Barb R. Thomasd, William Schroederf, Shawn D. Mansfieldg, Aine L. Planth and Malcolm M. Campbell, "Clone history shapes Populus drought responses," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Published Online July 11, 2011

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Galileo Galilei; physicist; scientific method; classical mechanics; mechanical properties; Two New Sciences (1638); square-cube law; volume; surface area; animal; science fiction films; Gustave Dore; Dante Alighieri; Inferno; Titans; Wikimedia Commons; Tree; bonsai; Sequoioideae; Sequoia sempervirens; suction; water; meter; capillarity; nanometer; nm; scientist; Department of Earth Atmosphere and Planetary Sciences; Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts); Santa Fe Institute (Santa Fe, New Mexico); Portage, Inc. (Los Alamos, New Mexico); Department of Physics; Institute for Physical Science and Technology; University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland); Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, New Jersey); continental United States; Southwest; Northeastern United States; Northeast; Northwestern United States; Pacific Northwest; mathematical model; precipitation; rainfall; humidity; temperature; insolation; forest; leaf canopy; albedo; climate model; xylem; Phloem; arboreal vascularia; fractal network; New England; logging; theory; climate change; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; carbon sequestration.