Is Religion becoming Extinct?

April 1, 2011 There's much evidence in favor of larger entities enriching themselves at the expense of smaller entities. We have large corporations buying smaller ones to make even larger corporations (with less resulting competition and an extra burden to the consumer, but that's another story). We have the folk wisdom of the sayings, "It takes money to make money," and "The rich get richer and the poor get poorer." The later even appears in the Bible (Matthew 13:12):"For whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance: but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath."This principle is at work also in a process called Ostwald ripening. Forty years ago, I became an expert on Ostwald ripening for the simple reason that it was of special interest to one of my professors in graduate school. I was certain he would ask a question about it in my comprehensive examination for entrance into the PhD program; he did, and the rest is history. Ostwald ripening is simply the idea that small crystals in a solution will dissolve, and larger crystals will grow. Wilhelm Ostwald, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1909, observed this phenomenon in 1896. Ostwald, who was awarded the Prize for "his work on catalysis and for his investigations into the fundamental principles governing chemical equilibria and rates of reaction," was a founder of the field of physical chemistry, along with Svante Arrhenius and Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff.

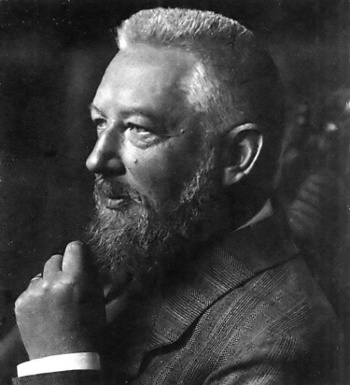

| Wilhelm Ostwald. Ostwald won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1909. (Photograph via Wikimedia Commons) |

Religious affiliation as a function of time for the Schwyz Canton in Switzerland and the Netherlands. Red dots are census data, and black lines are model fits. (Fig. 1 of Ref. 1, modified)[1]

The decline in church attendance is not news. The famous "Is God Dead?" cover story of Time magazine was published in 1966, although the import of the article was more about theologians' response to secularism rather than the decline in religion, per se. The phrase, "God is dead," goes back to the nineteenth century and Friedrich Nietzsche. This gave rise to a memorable tee-shirt script, "God is dead - Nietzsche. Nietzsche is dead - God."

A paper posted on the arXiv physics preprint server by researchers at Northwestern University (Evanston, Illinois) and the University of Arizona (Tucson) applies the tools of statistical mechanics and nonlinear dynamics to modeling the decline of religion.[1]

Like the Ostwald ripening example, they look at the problem as a competition between groups for membership, these groups being church-goers and the unaffiliated. Essentially, if members see more utility is being in one group than the other, they are inclined to jump ship. If there's more utility in being unaffiliated, religion will become extinct.

The modeling was based on census data from nine countries for which information on religious affiliation is collected; namely, Australia, Austria, Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Switzerland.[1-2] The data across all countries could be modeled by a growth law that used a single parameter for each country that quantified the perceived utility of adhering to a religion. The modeling showed that religion was on a path towards extinction in all countries, albeit at different rates as determined by the parameter (see figure).[1]

Religious affiliation as a function of time for the Schwyz Canton in Switzerland and the Netherlands. Red dots are census data, and black lines are model fits. (Fig. 1 of Ref. 1, modified)[1]

The decline in church attendance is not news. The famous "Is God Dead?" cover story of Time magazine was published in 1966, although the import of the article was more about theologians' response to secularism rather than the decline in religion, per se. The phrase, "God is dead," goes back to the nineteenth century and Friedrich Nietzsche. This gave rise to a memorable tee-shirt script, "God is dead - Nietzsche. Nietzsche is dead - God."

A paper posted on the arXiv physics preprint server by researchers at Northwestern University (Evanston, Illinois) and the University of Arizona (Tucson) applies the tools of statistical mechanics and nonlinear dynamics to modeling the decline of religion.[1]

Like the Ostwald ripening example, they look at the problem as a competition between groups for membership, these groups being church-goers and the unaffiliated. Essentially, if members see more utility is being in one group than the other, they are inclined to jump ship. If there's more utility in being unaffiliated, religion will become extinct.

The modeling was based on census data from nine countries for which information on religious affiliation is collected; namely, Australia, Austria, Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Switzerland.[1-2] The data across all countries could be modeled by a growth law that used a single parameter for each country that quantified the perceived utility of adhering to a religion. The modeling showed that religion was on a path towards extinction in all countries, albeit at different rates as determined by the parameter (see figure).[1]

| All data on religious affiliation as a function of time. Time has been rescaled to overlap these data sets. Red dots are data points for regions within countries,and blue dots are fir entire countries. The black line shows the model. (Fig. 2 of Ref. 1)[1] |

"The idea is pretty simple.. It posits that social groups that have more members are going to be more attractive to join, and it posits that social groups have a social status or utility."Wiener presented the study at the American Physical Society 2011 March Meeting in Dallas, Texas.[4] The study was funded, in part, by the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

References:

- Daniel M. Abrams, Haley A. Yaple and Richard J. Wiener, "A mathematical model of social group competition with application to the growth of religious non-affiliation," arXiv Preprint Server, January 14, 2011.

- Jason Palmer, "Religion may become extinct in nine nations, study says," BBC News, March 22, 2011.

- Daniel M. Abrams and Steven H. Strogatz, "Linguistics: Modelling the dynamics of language death," Nature, vol. 424, no. 6951 (August 21, 2003), pp. 900 ff.. PDF file here.

- Richard Wiener, Haley Yaple And Daniel Abrams, "Modeling the decline of religion," Abstract B14.00005 of the American Physical Society 2011 March Meeting (Dallas, Texas) NOTE - 1184 page PDF file!

- Jason Palmer, "Religion may become extinct in nine nations, study says," BBC News, March 22, 2011.